Everything you need to know about CPF

(This article is published bilingually, with the 中文版 following the English edition)

CPF: A Pillar of Retirement Planning

The concept of a legal retirement age is, frankly, a bit absurd. Imagine a 35-year-old software engineer, laid off and unable to find work, trying to make sense of a rule that says they can only “officially retire” at 60. In mainland China, the retirement age really has two meanings: the age you stop working and the age you start receiving your pension. The debate around raising the retirement age isn’t about the first—it’s about the second. For those in jobs with lifetime employment guarantees, a higher retirement age can even be seen as a perk.

Singapore, however, approaches this differently. From the start, it separated the age when people stop working from the age when they start collecting retirement payouts. You might stop working without receiving retirement benefits yet. Or, conversely, you might keep working while also drawing on your retirement funds. The two are not mutually exclusive.

Today, let’s focus on Singapore’s version of social security and retirement pensions. While the age at which one stops working is significant, in a world where job security is increasingly fragile, it’s less critical. As in the earlier example, if someone has already been out of work long before reaching the official retirement age, that age becomes meaningless. On the flip side, many Singaporeans in their 70s or 80s continue to work, whether by choice or necessity. The official retirement age doesn’t constrain them.

Understanding CPF Accounts: Ordinary, Special, MediSave

Strictly speaking, Singapore doesn’t have a state-run, pay-as-you-go pension system. Instead, its retirement framework can be summarized as: mandatory savings and annuity insurance.

The mandatory savings portion works similarly to China’s social insurance system. Each month, both employers and employees contribute a percentage of the employee’s salary into their Central Provident Fund (CPF) account. The exact percentage varies by age, but for younger workers, employees contribute 20% of their salary while employers add another 17%.

It’s important to note that Singapore’s CPF isn’t the same as China’s housing fund—it’s more like a combination of social security, health insurance, and housing fund all rolled into one. Contributions are divided into three accounts:

Ordinary Account – Primarily used for housing, but it can also fund retirement payouts later. The account is flexible: the funds can be used for down payments or monthly mortgage payments. Essentially, until your housing loan is fully repaid, this account acts almost like a checking account.

Special Account – Dedicated to retirement savings. Funds here cannot be withdrawn before the age of 55, and even then, there are strict rules about how much can be withdrawn. This is the main source of retirement payouts starting at 65.

MediSave Account – Reserved for medical expenses and health insurance premiums. Its use is highly restricted, and there’s no age at which the funds become fully withdrawable.

The monthly allocation to these accounts is roughly 60% to the Ordinary Account, 20% to the Special Account, and 20% to MediSave, although this shifts with age. The general principle is to prioritize housing needs when young and focus on retirement and healthcare later.

Like China’s system, CPF contributions are capped. Even if someone earns $10,000 a month, contributions are calculated based on a cap of $6,000 (which is gradually being raised to $8,000). There are several key differences from China’s model:

Every individual has their own account—there’s no pooling of funds or intergenerational transfer.

CPF savings earn interest: 2.5% for the Ordinary Account and around 4% for the other two accounts, which are tied to long-term government bond yields.

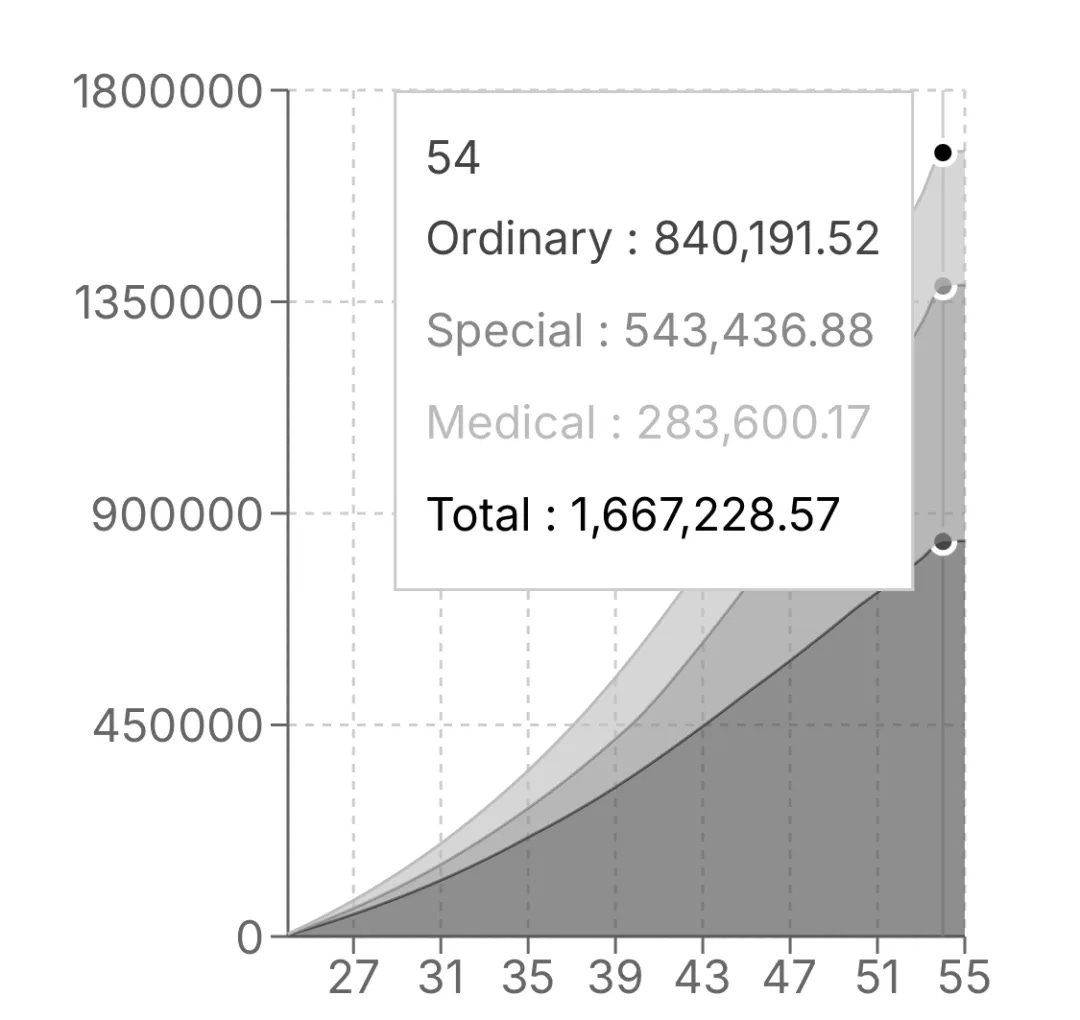

With mandatory savings of 37% of monthly salary and compound interest of around 3%, the long-term returns can be significant. For example, if someone starts working at 23 with a monthly salary of $4,000, receives two months’ bonus annually, and sees an average salary increase of 4% per year, their CPF balance could grow to SGD 1.66 million by age 55. That’s nearly SGD 50,000 in annual interest alone by that point.

Of course, inflation cannot be ignored. The SGD 1.67 million projected in 30 years will not have the same purchasing power as it does today. Assuming an average annual inflation rate of 2.5%, that amount would be equivalent to about SGD 800,000 in today’s terms. However, it’s worth noting that the Special and MediSave Accounts are pegged to long-term government bond rates, which helps partially offset inflation. Meanwhile, most people's Ordinary Account savings are typically used for housing, tying those funds to real estate prices.

Another important factor is generational differences. The earlier example assumes a millennial born in the 2000s working for 30 years, with a starting salary of SGD 4,000—a reasonable estimate for that generation. In contrast, for earlier generations, starting salaries may have been just a few hundred dollars. Over decades, this makes it difficult for them to accumulate the same level of CPF savings.

A look at the median CPF balances for different age groups shows that savings do not increase steadily with age. Balances peak among those aged 45–50, typically falling within the range of SGD 300,000–400,000. For those over 50, balances drop sharply. Without intergenerational transfer mechanisms, most elderly Singaporeans have very modest CPF savings for retirement.

The CPF Milestone at 55: Retirement Account Creation

Turning 55 is a major milestone in Singapore’s CPF system. At this age, a Retirement Account is created, funded by transferring money from your Ordinary and Special Accounts. The amount transferred depends on the retirement plan you choose: Basic, Full, or Enhanced Retirement Sum. For 2024, these amounts are as follows:

Basic: SGD 102,900

Full: SGD 205,800 (default)

Enhanced: SGD 308,700

These thresholds increase annually due to inflation and longer life expectancy. Younger workers will need to save more to fund their retirement.

After transferring the required amount, any leftover money remains in the Ordinary Account, where it can be withdrawn immediately, no strings attached. For example, if someone has SGD 500,000 across their Ordinary and Special Accounts at 55 and opts for the Full Retirement Sum (SGD 205,800 in 2024), they can withdraw the remaining SGD 294,200 right away.

However, not everyone reaches the Full Retirement Sum. According to government statistics, only half of Singaporeans turning 55 in 2022 managed to save SGD 200,000 in their CPF. For the other half, all their CPF savings are absorbed into their Retirement Account, leaving nothing withdrawable.

The CPF system also accounts for property ownership. If you own a home with a long lease, you can opt for a lower retirement sum, like the Basic Retirement Sum, because your housing acts as a form of financial security. This flexibility helps people who have invested heavily in property manage their retirement savings more effectively.

CPF LIFE: Monthly Payouts for Life

Once the Retirement Account is created, it continues to earn 4% interest annually until payouts begin at 65. If someone has SGD 200,000 at 55, it will grow to nearly SGD 300,000 by 65. This money then funds monthly payouts for life, creating what’s effectively an annuity insurance.

Here’s how much you can expect to receive under different scenarios:

Basic Retirement Sum: SGD 790–850 per month.

Full Retirement Sum: SGD 1,470–1,570 per month.

Enhanced Retirement Sum: SGD 2,140–2,300 per month.

If you delay payouts past 65, the monthly amounts increase. The latest you can start is at 70, maximizing your payouts.

What’s interesting—and quite comforting—is that CPF ensures you (or your heirs) won’t lose money. If you pass away shortly after payouts begin, your remaining balance (principal + interest) is refunded to your beneficiaries. Conversely, if you live to 100, you’ll continue to receive monthly payouts, even if you’ve “outlived” your savings.

This balance is achieved through risk pooling. Essentially, the interest accumulated after age 65 is redistributed among CPF members. This collective approach prevents the nightmare scenario of running out of retirement funds in old age, making CPF both a savings scheme and a safety net.

CPF Interest Rates: A Balancing Act

Now, about those CPF interest rates. The system isn’t just about stashing money in a government fund. It’s essentially a deal where the government borrows money from CPF contributors at 2.5% (Ordinary Account) or 4% (Special and MediSave Accounts) and invests it through entities like GIC and Temasek. The government shoulders all investment risks, guaranteeing the interest rates regardless of market conditions.

These rates have been a focal point of public debate. During low-interest periods, they were seen as relatively generous. For example, the 4% minimum rate for Special and MediSave Accounts often exceeded the yield on 10-year Singapore government bonds. However, as global interest rates rise, some Singaporeans now feel that CPF rates are less competitive.

The CPF system does offer flexibility: if you’re unhappy with these rates, you can invest your savings elsewhere, such as in stocks, bonds, or funds. Even low-risk options, like bank fixed deposits, can sometimes yield better returns than the 2.5% Ordinary Account rate.

Inflation and Retirement Planning Challenges

What sets Singapore’s retirement system apart from many others, like China’s, is its non-reliance on intergenerational transfer payments. This choice reflects the government’s emphasis on personal responsibility and its conservative fiscal philosophy.

However, this system isn’t without challenges. For today’s seniors, low wages and limited CPF contributions during their working years mean many lack sufficient retirement savings. To address this, the government has rolled out targeted support schemes for older citizens. But even with such aid, many retirees depend on three main sources:

Family support – It’s customary in Singapore and Malaysia for children to provide monthly allowances to their parents.

Property income – Renting out a room or downsizing can help supplement retirement funds.

Continued employment – Many seniors choose or need to keep working to make ends meet.

For younger and middle-aged Singaporeans, the lack of intergenerational transfer reduces the financial burden of supporting older generations. But it also means they must shoulder the full responsibility of saving enough for their own retirement. The big challenge? Fighting inflation over decades and accumulating sufficient savings.

For example, the Full Retirement Sum has quadrupled over the past 30 years, from SGD 40,000 to SGD 200,000. This isn’t just about inflation—rising life expectancy means that retirement savings must stretch further.

Final Thoughts

Singapore’s CPF system has many well-thought-out features, but no system can predict or promise against the uncertainties of decades ahead. For individuals, CPF is a strong pillar of retirement planning, but it’s not the whole solution.

Here are some risks to keep in mind:

Policy changes: CPF rules, including the 4% guaranteed interest rate for Special Accounts, are reviewed annually and could be adjusted.

Delays in payouts: As life expectancy increases, the retirement age may continue to rise.

Currency strength: While Singapore’s government is highly unlikely to default, long-term risks to the Singapore dollar’s purchasing power remain.

In the end, retirement planning requires diversification. While CPF provides a reliable foundation, it’s wise to manage risks by spreading your “eggs” across multiple baskets—other investments, property, and, most importantly, personal health. After all, the ultimate safety net is not just a financial one but also the ability to stay active and adapt to changing circumstances.

(Disclaimer: This article was originally written in Chinese and translated into English by the almighty ChatGPT with manual editing. In case of any discrepancies, the original Chinese version should be considered the preferred source. Below is the Chinese version)

(一)

法定退休年龄是个吊诡的概念。一个35岁被裁且找不到工作的程序员,如何理解60岁才“法定退休”这件事?在中国大陆的语境里,这里的退休年龄其实包含两层意思:停止工作的年龄以及开始领退休金的年龄。而延迟退休之所以引发争议,是因为后者而不是前者。前者对那些事实上采用终身雇佣制的工种来说,其实是一种福利

之所以要说到这个,是因为新加坡的退休和养老系统,从一开始就把这两个年龄剥离开来了,停止工作的年龄,不等于开始领退休金的年龄。一个人可能停止工作了,但是还没开始领退休金。一个人也可能既在工作又在领退休金,这两者并不矛盾

今天我们只聊新加坡版本的社保和退休金。停止工作的年龄这事尽管也重要,但在雇佣关系越来越脆弱的当下,实际上也不是特别重要。如本文一开始的例子,如果一个人在法定退休年龄之前已经没有工作了,规定一个退休年龄意义不大。反之,新加坡有很多七八十多岁的老人仍然或主动或不得已地在工作——法定的退休年龄并没有限制住他们

(二)

严格来说,新加坡并没有国家统收统支的养老金制度。其养老机制,可以简单总结为八个字:强制储蓄和年金保险

强制储蓄和中国的五险一金类似,每个月雇主和员工会按照收入的比例把钱存进员工的公积金户头。具体比例取决于年龄,对于年轻人来说,一般是员工交20%的月工资,雇主交17%

值得注意的是,这里的公积金并不等于中国大陆的住房公积金,而是接近于社保、医保和住房公积金的集合。具体来说,钱存进了三个户头:

普通户头:主要用于买房,老了也可以用来发退休金。买房的话,可以用来付首付也可以用来还月供。这部分的比例最高,钱的流动性也最好。只要买了房,在还完房贷之前,普通骨头实际上约等于活期存款,可以随时拿出来

特别户头:主要用于退休。55岁前一分钱都不可以取出来,55岁之后能不能取、能取多少,有一套复杂的规则,下文会提及。这个户头是65岁后用于发养老金的主力

保健户头:主要用于看病开支和买医疗保险。用途很受限且不存在一个可以全额取出来的年龄点

这三个户头每月进账的比例大约是60%:20%:20%,随着年龄增长会有所调整。基本原则是年轻时偏重住房需求,年老时注重退休和医疗

和中国类似,公积金缴纳也是有顶限的。一个人月薪十万,也只能按6000来缴纳(最近几年正慢慢过渡到每月8000)。这里有几个和大陆社保和公积金比较不同的点:每个人有自己的账户,不搞统筹也不搞代际、跨省转移;钱存公积金是有利息的,普通账户是2.5%,另外两个户头和长期国债绑定,多年以来都在4%左右(10年期国债利率+1%)

相当于月工资37%的强制储蓄再加3%左右的复利,长期来看还是挺可观的。假设一个人23岁大学毕业,起薪4000新币,每年领两个月花红,平均涨薪4%,这算是一个普通新加坡人的职场轨迹。那么到他55岁时公积金里面的钱会达到166万新币(一新币约等于5.4人民币)。55岁每年的利息就超过5万

当然,这里不能忽视的是通胀。三十年后的167万到底相当于今天的多少钱是个问题。以长期通胀率年化2.5%考虑,167万约等于今天的80万。不过,特别户头和保健户头的利率是和长期国债利率挂钩的,一定程度上也钩住了通胀。而大部分人的普通户头,都拿去买房了,这部分资产就和房价绑定了

另一个要考虑的点,是代际的差异。例子里考虑的是个00后工作三十年的预测。对于00后,起薪4000新币是个合理的假设。但对于上一代人,初入职场时工资可能只有几百块。那么几十年下来,也不太可能攒到百万新币。下图是每个年龄段的新加坡人其公积金存款的中位数。可以看出,存款并不是随年龄递增的。45-50岁年龄段的中位数存款最多,在30-40万之间。45岁以上的存款迅速递减。由于没有代际转移,大部分新加坡老年人的退休金其实非常少

图源:Seedly

(三)

55岁是个重要的时间点。年满55岁时,公积金里面会新增一个退休户头,从普通户头和特别户头划钱进去,为65岁退休作准备。划多少钱取决于你选择了哪个版本的退休金,基本版最少,默认是完整版,如果想拿更多退休金,可以选加强版。以2024年为例,当年的基本版是存入10.29万新币,完整版是20.58万新币,加强版是30.87万新币(2025年起会变成基本版的4倍)。这些数值每年都会调高,一来因为通胀二来因为人均寿命越来越长,越年轻的人需要越多的钱来养老

如果把钱放进退休户头后,还有剩余的话,这些钱会全部放回普通户头,然后在55岁时就可以无条件地取出。举个例子,一个人55岁普通加特别户头里面有50万,他选择了完整版的退休金配套,往退休户头存进20.58万新币,那么剩下的29.42万新币就从此自由了,变成了活期存款。当然,大部分人仍然会选择把钱放在普通户头,赚取2.5%的利息

不过,显然并不是每个人在55岁都能凑齐完整版的退休金。按照政府的统计,2022年满55岁的新加坡人里面,能攒够大约20万新币的只占一半。对于剩下的一半人口,全部的公积金进了退休户头后,基本一分钱不剩了

此外还有一点,考虑到很多人的普通户头都用来买房子,政府也允许有房产且房契足够长的人,少往退休户头打钱。举个例子,一个人55岁时户头里面有15万,介于基本版和完整版之间。如果没有房产,那么全部的钱都要进退休户头,但如果有房产,则可以只选10.29万的基本版

(四)

退休户头55岁时创立,然后从55岁到65岁会一路赚取4%的利息。假设55岁时有20万,到65岁时就变成将近30万。这30万就会用来发退休金。交了一辈子公积金,最大的问题可能就是:退休时每月可以领多少钱?

下面以2022年满55岁的小明为例,说明各种情况下分别能拿多少钱。

情况一:小明2022年刚满55岁,普通和特别户头的钱刚好等于当年的完整版数额19.2万新币,全部划入退休户头。这部分钱继续拿4%的利息,到65岁时是2.9万新币。从65岁起,小明每月可以拿1470-1570新币,直到去世

情况二:小明2022年满55岁,退休户头里面有9.6万新币(当年的基本版数额)。从65岁起,他每月可拿790-850新币

情况三:小明55岁时退休户头里有28.8万新币(当年的加强版数额)。从65岁起,他每月可拿2140-2300新币

在65岁时也可以选择暂时不拿退休金。越晚开始拿钱,后面拿的时候每个月退休金就越高,最晚可以到70岁才开始拿

此外很重要的一点,是新加坡的养老金制度,保证一个人和他的继承人能拿到的钱,不会比65岁时投入的钱少。极端的例子,小明65岁时退休户头有28.89万新币,退休金每月1500,领了一年后小明去世了。则小明的继承人可以拿回288900-1500×12=27.09万新币

新加坡的养老金制度,也保证了即使一个人活到两百岁,也有退休金拿。换句话说,如果一个人寿命足够长,他拿到的总退休金,是会超过他65岁投入的本金的。简单估算的话,“够本”的年龄线大约是81岁

上面两点看似矛盾:既然早逝不会亏,而长寿又赚了,且财政不补助,那多出来的钱是从哪里来的?其实秘密就在于利息。通过风险均摊(risk pooling),将本金在65岁后累积的利息全员共享。这种共享机制,避免了“人还在,但退休金已经没了”的悲剧。这就是为什么上文里说这是一种年金保险,因为它不只是把年轻时存的钱在年老时发出来,而是带有保险属性,是一种小型的大锅饭。当然,要指出的是,共享部分仅限于65岁后的利息,本金和65岁前累加的利息,是不共享的

(五)

公积金有利息这件事,也很值得说一说。强制储蓄收上来的钱,并不是放在池子里不动。本质上,它是一种特别国债:政府以2.5%/4%的利率向民众借钱,然后用于主权投资。当然,民众不承担投资的风险,这种特别国债是有政府税收兜底的

利息是公积金制度的基石。如果只有强制储蓄而没有利息,那么这种储蓄在通胀面前就显得非常愚蠢。公积金利率在新加坡向来也是争论焦点。在低息时代,2.5%和4%的利率相对还算吸引人。特别和保健户头的计算公式,虽然是十年期国债收益率+1%,但政府过去十几年都设置了4%的保底利率(在这轮升息周期之前,十年期国债收益率远低于3%)

到了最近的升息周期,民众不免就对这个利率不太满意。但公积金有一个比较人性化的设定,就是如果你觉得利率太低,可以把钱拿去自己投资。比如普通和特别户头的钱,都可以拿去投资股票、债券或者基金等等。这种投资也不一定要是高风险投资,比如2023年有段时间,本地银行的定存利率,要高于普通户头的2.5%,很多民众就选择把钱存到银行

(六)

不难看出,新加坡的养老制度,和中国大陆的最大区别,就在于是不是搞代际转移支付。新加坡的选择并不意外,因为政府长期以来的思路,一直是强调个人责任和坚持保守的财税制度

也不难看出,在这种制度下,现在七八十岁的一代人往往没有足够的养老金,因为早年的经济水平、工资水平和劳动参与率都比较低。也因此,政府近些年的很多政策,都是在定向帮助年长人士。不过政府的支持毕竟有限,在新加坡的文化里,养老一靠子女(在新马,每月给父母家用是一种惯例),二靠房产(比如出租一间房补贴家用),三靠自己打工

不搞代际转移,当然也对现在的年轻人和中年人更友好。但是,这种情况下,年轻一代也不是毫无风险。最大的风险在于长时间窗口之下,如何战胜通胀,并且存够钱。以完整版的退休户头金额为例,过去三十年其金额增长了4倍,从4万涨到20万。也就是说,按照政府的评估,65岁后要维持类似的退休生活,65岁前要攒的钱,现在比30年前要多4倍。这里面倒不是说物价涨了4倍,而是通胀的同时人均寿命也涨了,同样的钱摊薄到更长的晚年,每年的养老金就变少了

总体来看,新加坡的公积金虽然有很多科学的设计,但人算不如天算,没有一个政府能对四五十年后的事情做出充分承诺。作为个人,我倾向于把公积金作为养老的一部分,充分信任政府,但同时不能无视风险

比如说,公积金的几乎所有关键条款,都不受宪法保护。随着时间的推移,这些条款都可能修改。特别户头的4%的兜底利率,其实是每年都要重新审视的,政府并没有保证能长期负担4%的利率;又比如,随着人均寿命的不断提高,65岁开始领退休金也不是不可能推迟。更大的风险来自于国运和地缘政治:尽管新加坡政府几乎不可能对特别国债违约,但以五十年的时间窗口来看,新币是不是能一直保持强劲的汇率和购买力?

80后90后也算是一代婴儿潮。在人口萎缩的现实面前,在哪个国家养老都不容易。科学规划,正确评估风险,把鸡蛋放在多个篮子算是“术”,但终极的出路可能要靠心理按摩:锻炼身体,降低预期,放弃幻想,时刻做好终身打工的准备